Meet Estwick Evans (1787-1866)

HISTORY MATTERS

Even local historians stare back blankly when asked about Estwick Evans. In his 1859 Rambles About Portsmouth, journalist Charles Brewster called Evans “the eccentric,” but without explanation. No explanation was needed.

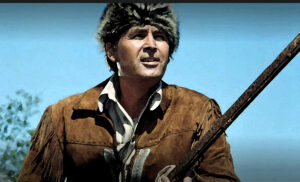

Back then everyone in town knew about the eccentric Portsmouth-born New Hampshire lawyer. In the winter of 1818, Evans donned a buckskin suit, tucked two pistols in his belt, and, accompanied by two large dogs, disappeared into the wilderness.

The western American border in 1818 was still pretty much the Mississippi River. Fifteen years earlier Thomas Jefferson had acquired the so-called Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million, nearly doubling the size of the new nation. Lewis and Clark had mapped their way to the Pacific coast. But as Evans was packing for his solo adventure, there was, as yet, no west coast (it belonged to Mexico), no Oregon territory, and no Texas.

Evans’ journey extended to the Great Lakes, down the Mississippi River, and back home to New England. Upon his return, friends pressed him to write an account of his trip, which he did. A Pedestrious Tour of 4,000 Miles came out the following year in 1819, just as Florida was being added to the United States map. The archaic word “pedestrious” means Evans made the trip on foot.

Why did he do it?

Details about Estwick Evans, the man, are scarce. He was reportedly born in 1787 at a farm on Sagamore Creek (once called “Witch Creek”), a scenic salt-water inlet in Portsmouth. The Martine farm cottage off Little Harbor Road was built as early as 1700. According to local lore, Prince Louis Philippe stayed at the Martine cottage for a week in 1798 while traveling in the United States. Phillippe later became king of France. A prominent Boston architect bought the property and expanded it in the early 20th century – and it survives to this day.

So we know as much about his birthplace as we know about the eccentric Mr. Evans. And extracting biographical details from his “Pedestrious Tour” is no easy task. “I shall speak as little of myself as will be consistent with the nature of the publication,” Evans declared in the preface to his travelogue.

We know from public records that Evans was largely self-educated. He was admitted to the New Hampshire Bar in 1811 and became a champion of poor working-class clients. Rejected for service in the War of 1812 due to an unspecified disability, Evans clearly longed to prove his physical stamina to himself and perhaps to others. He also hoped to better himself intellectually through a dangerous, even foolhardy, mission. “The beaten track,” he wrote, “is not always the field for improvement.” He also wanted to see the vast American wilderness before it disappeared.

As early as 1818, Evans implied, Americans were already getting soft, cowardly and complacent. City dwellers were losing touch with Nature. While there was much depravity in the savage world, he wrote, there was also plenty of depravity in civilized society.

“I wished to acquire the simplicity, native feelings, and virtues of savage life,” he explained, “to divest myself of the factitious habits, prejudices, and imperfections of civilization…and to find amidst the solitude and grandeur of the western wilds, more correct views of human nature and of the true interests of man.”

To further test his mettle, Evans began his journey during the “season of snows.” Hiking in harsh winter weather offered him “the pleasure of suffering, and the novelty of danger.”

The journey begins

On Feb. 2, 1818, Evans set out with his faithful dogs from a friend’s house near Concord, NH. He was strangely attired in a “close dress” of buffalo skins with exterior shoulder pads made from long buffalo hair to keep off the rain. A leather case under one arm held a brass charger for his cap and ball revolvers. A case under his other arm contained gunpowder. Around his waist he carried a “brace of pistols” and a “dirk” or dagger, as well as ammunition. He also wore an “Indian apron” made of bearskin in which he carried a compass, maps, his journal, shaving materials, a small hatchet and a fire-starting device. He had a fur hat, fur gloves, and deerskin moccasins. He carried a six-foot-long rifle with money hidden throughout his clothing.

It’s no wonder the adventurer from New Hampshire evoked a mixture of fear, curiosity and laughter as he wandered in and out of towns, forts, and Indian reservations en route to the frontier. He was mistaken for a British spy, for an Icelander, and for Napoleon in disguise. Others thought he might be a wizard.

Evans slogged about 20 miles a day “through trackless snows and over tremendous mountains.” Sleeping in a tent in deep snow he met “a great variety of characters “from the savage of the wood to the savage of civil life.” When challenged, he fought back. When offered a bed, a shed, or a spot by the fire, he readily accepted and paid for his lodging. The poorer his hosts, Evans noted, the less likely they were to accept his money.

By March 20, Evans had reached Detroit, but not without hazards. While still in New Hampshire he had become exhausted struggling through snowdrifts 10 feet deep. Vermont was so frigid and the winds so strong his ears froze. In New York, he suffered from a severe toothache. His feet swelled to twice their size. He broke through icy rivers and nearly drowned. Sleeping in the woods he was in constant danger from wild animals and from hunters mistaking the man in the fur coat for a bear. His two dogs, Tyger and Pomp, were killed by wolves outside Detroit.

The quixotic philosopher

These were wild times. Just six years before he arrived at Detroit, the frontier city had surrendered to British and Indian forces in the War of 1812. Along the way, he recorded the types of animals he saw, noted species of trees, the fertility of the soil, the situation of Native American tribes, the strength of rivers, and the nationality of pioneers flooding into the new territories.

In his memoir, Evans also mused about women’s rights, racial prejudice, life after death, the need for a standing American army, animal cruelty, and the evils of war. “The desire of great wealth,” he noted in his journal, except for charitable purposes, “is criminal. It is dictated by a spirit of luxury, by pride, by extravagance, by spirit of vain competition … by avarice.” He regretted that men are governed “more by feelings than by ideas.” And he observed that “little men create for themselves temples of fame, which the weight of a fly might crush.”

After further adventures in the Great Lakes region, Evans traveled on foot along the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where he made the last leg of his journey home to New Hampshire by sea. Having tested his mettle and after publishing his impressions, Estwick Evans got on with his career as a New Hampshire lawyer, or what he called “a limb of the law.” He married and even served briefly in the state legislature. He moved to Washington, DC in 1829 where he served in various government offices. Evans wrote for The National Intelligencer, the dominant newspaper of the capital. He died in New York on November 20, 1866.

His only book, A Pedestrious Tour, though largely forgotten, is occasionally praised by scholars as a rare look at the frontier following the War of 1812. His entire account was reprinted in 1904 along with other American memoirs titled “Early Western Travels.” Despite his eccentricities, the editors of the eight-volume series pointed out that Evans’ comments about the frontier were “shrewd, eminently sane, and practical.” And for those intrigued by this curious work, it can be seen or downloaded for free from Google Books.

The greatest praise for Estwick Evans came from Robert Frazier Nash who mentioned the New Hampshire lawyer in his classic study Wilderness and the American Mind (1967). Like many following the Revolution and the War of 1812, Evans romanticized the American wilderness that seemed primitive compared to the growing cities and farms. Evans was “remarkable,” Nash explained because he “actually put his philosophy into practice” and then recorded his impressions of a rapidly changing nation.

“As a species,” Nash wrote, “we have been lousy members of the ecological neighborhood.” Estwick Evans, were he alive today, would certainly be an avid environmentalist. The importance of the wilderness, he wrote, was to make mankind feel “both humble and exalted” at the same time.

“How great are the advantages of solitude,” the New Hampshire lawyer wrote in 1818. “How sublime is the silence of Nature’s ever-active energies! There is something in the very name of wilderness, which charms the ear and soothes the spirit of man. There is religion in it.”

The unforgettable Kentucky frontiersman, Daniel Boone, died in 1820, the year following the release of the memoir by New Hampshire’s all-but-forgotten adventurer.

Copyright 2017 by J. Dennis Robinson, all rights reserved. Revised in 2025.

Understanding the Portsmouth African Burying Ground

Understanding the Portsmouth African Burying Ground

Leave a Reply