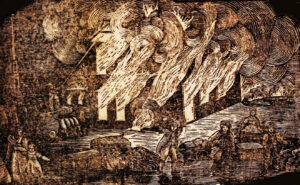

At the peak of Portsmouth’s shipping success as a world trade center, the fires of 1802 and 1806 transformed the heart of the city into a smoldering ruin. Only a forest of blackened chimneys stood along Daniel and Market streets once lined with wooden shops and homes. So when flames engulfed downtown Newburyport, Massachusetts on May 31, 1811, Portsmouth volunteers rushed south to help.

The fire had begun in “an unimproved stable” on Mechanics Row. It spread rapidly to the Newburyport market area and up State Street. Flames then moved in so many directions “as to baffle all exertions to subdue it.” The seaport lost many stores and dwellings that night, plus a church, the custom house, library and post office, four bookstores, and all four of its printing offices. Upwards of 90 families were left homeless as an estimated 250 Newburyport buildings, large and small, were destroyed at a cost of a million dollars (in 1811 currency). Arson was suspected, but no one was arrested.

Leather fire bucket brigades made little difference. A Portsmouth “fire engine” left over from 1792 was little more than a metal pump with two handles drawing water from a wooden trough on wheels. Volunteers could do little but clear away the wreckage. With no insurance, the city’s “sufferers” could only petition for charity. Contributions quickly trickled in from Boston, Salem, Portsmouth, and surrounding towns.

Arson suspected here too

Two years later, with the maritime economy in freefall and the nation again at war with England, downtown Portsmouth burned in “The Great Fire of 1813.” This time, it was Newburyport volunteers who joined surrounding towns in rushing to the scene. One man from Newburyport ran into a burning building and rescued a crying child. But once again, with 272 Portsmouth buildings destroyed, the real work was clearing up the rubble, attending to the homeless, and starting to rebuild.

Portsmouth’s worst blaze in 1813 reportedly began in Mrs. Woodward’s barn near Court and Pleasant streets, roughly the site of the South Church today. Legend says one of the guests at Mrs. Woodward’s boarding house gifted one of her servants with a bottle of wine. When the landlady confiscated the wine from her servant, he set fire to her barn in revenge. Blown by the wind, the fire ravaged buildings all the way up State Street until it reached the Piscataqua River.

Again, most of the victims were dependent on charitable donations from outside towns and churches. There were no fatalities in any of the three downtown Portsmouth fires and, despite rumors of arson, no one was arrested or prosecuted. A contemporary poem in the newspaper proposed that God would “smite the villain for his crime.”

Newburyport in 1820

Newburyport had all but recovered from its 1811 blaze when disaster struck again. Exactly why Stephen Merrill Clark set fire to the barn of Phebe Cross on August 18, 1820, was not revealed until the day of his execution. The second-worst fire in Newburyport history began on Temple Street and spread to neighboring stables. From there, it consumed a tenement building and three single-family homes. A few horses were killed in the fire, but there was no loss of human life.

Stephen Clark, the town’s 16-year-old “bad boy,” was instantly suspected. Known for his “propensity for mischief,” for lying and the constant use of profanity, Stephen had been arrested for assaulting an elderly man. His elderly father, Moses Clark, could no longer control him. His brother had tried to apprentice him as a cooper, but without success. Stephen was known to keep company with a “person of lascivious behaviour” named Hannah Downes. And it didn’t help his case when, at his father’s urging, Stephen disappeared from Newburyport soon after the fire.

It was Hannah, when confronted by the police, who said Stephen Clark had set the fire. Returning to Newburyport, the boy was arrested and, according to his lawyer, confessed “under duress” to the crime of arson.

A capital crime

While in jail, the teen reportedly threatened and swore at his captors. Too small for standard manacles, he was able to slip out of his restraints until smaller, child-size shackles were custom-fitted.

At his trial in February 1821, Stephen said he was innocent. His lawyer argued that, beyond the word of a prostitute and the boy’s forced confession and bad reputation, there was no evidence against him. Stephen’s father provided an alibi, claiming his son with home with him on the night of the fire. The jury found the boy prisoner guilty, but suggested leniency due to his age.

By 1805, the state of Massachusetts had softened many of its harsh Puritanical punishments. Prisoners could no longer be whipped, branded, their ears cropped or their fingers cut off. But the death penalty was still in play for crimes of murder, rape, burglary, treason, and arson. When Stephen learned he was to be executed, he made a desperate but failed attempt to bribe is jailer. He also tried to drill his way through the jaile wall with a hammer, apparently smuggled in by friends.

But as the day of his execution approached, Stephen Clark’s spirit broke. He went from buoyant to listless. The rebellious and wily prisoner, according to official reports, was “softened” by the “benevolent and pious endeavors” of two Christian ministers. He could confess his sins and be hanged, or roast in the eternal fires of Hell, they told him.

Shun my fate

Three months shy of his 17th birthday, Stephen Merrill Clark was executed in Salem on May 1821. He went to the gallows, we are told, “in a devout and religious state of mind.” Typical of the era, his heavily attended execution was publicized as a warning to future criminals.

The night before his execution, Stephen admitted that he had taken a piece of cloth about two feet long from his father’s house, soaked it in rum and brimstone, lit it with a cigar and and put it in some hay in the barn belonging to Phebe Cross. He also started a fire under the stairs with a candle.

But why, he was asked? The idea, Stephen confessed, came from Hannah Downes. The one person he cared for was offended at the way people in Newburyport talked about the two of them being together. Hannah suggested he should get revenge on the town by setting the fire. “She urged me to commit the act,” he said. He protested to her at first, but finally gave in.

The hanging of young Stephen Clark for starting a fire in which there were no fatalities helped focus the public debate over “capital murder” in Massachusetts. By 1852 the death penalty had been reduced to acts of murder and treason.

In his final hours the young prisoner said he held no grievances toward the people of Newburyport, or toward the judge and the jurors who had condemned him to die. He grew emotional when reminded of the pain he had caused his aged parents. In a written confession, as was the custom, he warned other youths to listen to their parents and to shun his evil ways.

He might be considered the only casualty of the five horrific fires that melted the heart of two sister seaports. Marching to the gallows the frightened and desperate boy turned to the two clergymen at is side. “You will take care of my body, won’t you?” he begged. Moments later Stephen Merrill Clark was launched into eternity.

PRIMARY SOURCE: “Account of the short life and ignominious death of Stephen Merrill Clark,, who was executed at Salem on Thursday the tenth day of May, 1821 at the early age of 16 years and 9 months, for the crime of arson. Salem, MA”: Published by T.C. Cushing. Massachusetts. 1821.

Copyright 2019 by J. Dennis Robinson, all rights reserved.

Tobias Lear: George Washington’s Troubled Secretary

Tobias Lear: George Washington’s Troubled Secretary

Leave a Reply