The Christmas spirit is real. It wells up in some form in every culture through recorded time, most often through the giving of gifts. But it isn’t that simple. There’s a catch, a twist and a gotcha. There is an algorithm of giving that flows through the best Christmas stories. The formula is as ancient as the Nativity, and older still. The gift is usually a surprise and the recipient is usually a child in need. From Tiny Tim to the Whos in Whoville, the child is vulnerable, often impoverished, always innocent.

The best Christmas stories are written for kids. Between the lines, they are all morality tales, crafted to instill the habit of charity and banish the sin of greed. We don’t need Charles Dickens or Dr. Seuss to see the formula at work. Here are three Seacoast authors who wrote from the heart in this classic tradition.

The joys of Anne Molloy

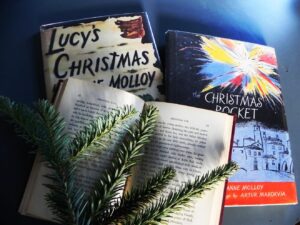

At least two of the 22 children’s books by Anne Molloy (1907-1999) evoke the holiday spirit. Married to a teacher at Phillips Exeter Academy, the mother of two, Molloy wrote her books in longhand, sitting on a sofa with her pages backed against a sturdy checkerboard. She then transcribed each manuscript on her husband’s Underwood typewriter.

Her stories were often inspired by travel and careful observation. In “The Christmas Rocket” (1957) the 10-year old son of a potter must carry a heavy basket of pots down a steep hill to sell to tourists in a small Italian town. Dino’s father and grandfather have painted each pot with colorful scenes. But there are no buyers that day. So there will be no new shoes for Dino, no meat for the holiday dinner, and no rocket to celebrate Christmas Day with his friends. Dino accidentally breaks the most beautiful pot on his way home. Despite his disappointment, he performs a good deed for a passing stranger, who turns out to become the family benefactor.

Molloy’s book, “Lucy’s Christmas” (1950), is set closer to home in the woods of Maine. On the opening page, 12-year-old Lucy Brackett’s home burns down. Her father, a logger, toils to earn enough money to rebuild their home by Christmas, but his earnings don’t match his dreams. Saddened that her little brothers will go without Christmas gifts, Lucy scratches a message on a piece of birch bark. She hides the note in the branches of a felled spruce that her father hopes to sell as a Christmas tree. Perhaps, she hopes, some wealthy buyer far away will find her note and send gifts to her brothers. But at the railroad station, the note falls from the branches. It is picked up by the stationmaster–and here comes the miracle – he calls his neighbors together. They build a new house for the Brackett family, just in time for Christmas. Like a message in a bottle, Lucy’s unselfish wish has inspired an entire town to charity.

Celia Thaxter’s “Piccola”

Anne Molloy is best known for her children’s book, “Celia’s Lighthouse,” about the girl whose family owned the Appledore Hotel at the Isles of Shoals. Celia Laighton Thaxter (1835-1894) also wrote stories for children while selling painted ceramic pots for tourists. Among her lesser known works is a heartwarming poem about a French girl named Piccola (although the name is usually Italian). Piccola’s family is so poor that her parents cannot afford a single Christmas present for her. But Piccola has absolute faith that St. Nicholas will bring her a gift. She leaves out her tiny shoe to receive the gift and then goes happily to bed on Christmas Eve.

It isn’t the best poetry, but Thaxter captured the drama and holiday spirit to perfection. As gray skies break on Christmas morning, Piccola is “just wild” with anticipation. She runs to see what the good saint has left in her shoe. She dances into the room, “happy as a queen,” to join her confused and guilt-ridden parents. “Never was seen such a joyful child,” Thaxter writes. But why? Then the poet reveals the miracle. A “little shivering bird” has flown in through the window and taken refuge in Piccola’s tiny shoe. The girl is enraptured with the gift.

What the reader sees as a coincidence or a miracle, Piccola sees as a validation of her good behavior in the eyes of St. Nicholas. The sparrow is a living reward, better than any manufactured toy, and she accepts her new pet with a thankful heart. Celia Thaxter, who once dined with Charles Dickens, accomplished her own version of “A Christmas Carol” in just 36 lines of poetry.

Charlotte Haven battles selfishness

Our final story comes from Charlotte Maria Haven (1825-1893), among the many descendants of Portsmouth minister Samuel Haven, who once chatted with George Washington near what is now Haven Park. A devout Christian, Charlotte Haven penned her book, “Christmas Hours” (1859), anonymously, in an era when women were not always accepted as serious authors. It is an often dark and depressing Sunday school book for the religious instruction of young girls. And yet, the message is hauntingly relevant in the turbulent 21st century.

As the book opens, a young female narrator rides 30 chilly miles through the snow in an open horse-drawn carriage to visit family members on Christmas Eve. The sleigh approaches Portsmouth as it looked in the days before electric lights and central heating. Haven writes: “Beautiful arches of evergreen are thrown across all the principal streets, standing in striking contrast with the soft white carpet of the earth beneath, while almost every window is wreathed in evergreen and holly, the poorer dwellings having at least a branch of spruce placed against a single pane. Bright fires blaze in rooms that seldom rejoice in such cheerful light.”

Despite the winter cold, everyone walks to the church on the hill, “festooned with wreaths and flowers,” where a chorus of a hundred children sing carols. The minister’s sermon is harsh. He warns the children not to take the “downward path” in life, since it leads only to “the world of woe, of suffering, and of death, with all its dread retributions.” Boys are warned not to be blasphemous, disrespectful, petulant or rude. Girls, the minister says, should try not to be vain, unkind, fashion conscious or overly angry. Those who seek only after riches, attention and power, they are told, will not be given the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Those were different times. Charlotte Haven’s message was for an era in which at least half of all children would not survive, so there was great concern among Christian families, for the souls of lost children. And indeed, two children die within the pages of Christmas Hours.

“Shall I ever conquer this selfishness?” a little girl worries, toward the end of the book. “There is no mystery in it,” her pious friend replies. Happiness depends on a single decision that we all must make. “Do you prefer to live for yourself alone, and seek your own pleasure regardless of any higher aim?”

The key to happiness in life is the same as the key to Heaven, her friend explains. One only has to “return good for evil.” If we love one another, Haven writes, then God loves us.

Once more, the little girl asks for clarification. How can she partake of the Christmas spirit? Haven’s conclusion can be taken literally or spiritually. All people, she explains, live in God’s house, in the same way that children live in the house of their parents.

“Suppose that your parents provided you with every outward comfort,” Haven says, and she could be speaking to our children today. Your parents provide “a pleasant house, abundance of food and clothing, books, flowers, music – but you lived wholly by yourself in your own room.” The child who rarely comes out of her room, the author says, can never truly come to know and love her parents. She is locked into herself.

Haven’s metaphor, of course, relates to her religious faith. The more one leaves the bubble we live in and does good deeds in the real world, she explains, the more one comes to know God and love others. All ego and selfishness are stripped away. We achieve a “victory over self,” and in doing so, we come to accept and care for others, even those who are different from us.

Selflessness, Haven tells us, is the essence of the Christmas spirit. Only those who elect to step outside their private world and set aside their own desires to work for others can feel it. And only through faith, she adds, can that fleeting holiday joy last a lifetime.

Copyright 2016 by J. Dennis Robinson, all rights reserved.

Abstracting the Seacoast

Abstracting the Seacoast

Leave a Reply