The more I delve intmoseso “Old Portsmouth,” the newer it looks. The Portsmouth Lyceum, for example, was a popular public lecture series in the 1800s. It closely resembled the TEDx Piscataqua River lectures presented annually at the Music Hall and 3S Artspace. TEDx talks feature “ideas worth spreading” and draw on top local talent. The Portsmouth Lyceum, named for an ancient Greek school of philosophy, had a similar mission. The goal was to spread “useful knowledge” to the community by tapping the smartest and most entertaining speakers in town. Sound familiar?

It all started in 1826 when an itinerant teacher and farmer named Josiah Holbrook gave a series of talks on science, art, literature, and politics in Millbury, MA. His adult students,mostly mechanics and other farmers, were hungry for a liberal education. The concept spread quickly in an era between wars. The United States, to the amazement of many, had survived 50 years, and Americans were feeling optimistic, experimental, and self-reliant.

Holbrook promoted his American Lyceum Society concept from town to town. He also urged communities to build libraries, compile town histories, improve teacher training, and include women equally in all lyceums. Lecture tickets should be inexpensive, Holbrook said, and speakers must be entertaining, so that their topics “be brought within the comprehension of the most untutored mind.” A smarter America, he reasoned, would become a more effective democracy.

By 1833, when Portsmouth officially joined the movement, there were 3,000 lyceum locations, most clustered in New England. With no movies, radio, or TV, that number quickly tripled. In his seminal study, The American Lyceum: Town Meeting of the MInd, the eminent scholar Carl Bode mildly chastised Portsmouth for its late adoption of the lyceum concept. Why did it take us seven years to get our act together? I dug deeper.

Female education

To my surprise I discovered a listing for the Portsmouth Lyceum in a NH Farmer’s Almanac published in 1826, the same year Josiah Holbrook conducted his first lyceum in Massachusetts. A document uncovered at the New Hampshire Historical Society in Concord sheds light on the mystery.

The first Portsmouth Lyceum, it turns out, was an experimental all-female school organized by a man with the unforgettable name of Rev. Orange Clark. A Canadian-born preacher, Clark drifted in and out of Portsmouth. He founded his girls’ school in rented rooms at Portsmouth Academy, the 1810-era brick building now home to Portsmouth Historical Society. The school offered a challenging five-year course of study on subjects from mathematics, logic, and Latin to astronomy, rhetoric, and ecclesiastical history for girls aged 11 and up. Three years later, apparently unable to find financial support, Orange Clark and his version of a lyceum were gone.

The records of the city’s second Portsmouth Lyceum, initiated in 1833, are stored in the vault of the Portsmouth Athenaeum. The inked pages in the leather bound journal are faded, but I immediately recognized one prominent founder. Charles Burroughs was rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church. Six years earlier, on October 26, 1827, Rev. Burroughs delivered a lecture entitled “Address on Female Education” to the students of Orange Clark. I found a published copy of the speech online.

The entire history of women, Burroughs told his female audience in 1827, had been “marked with degradation and oppression” due mostly to the “ignorance, overbearing pride, and licentiousness” of men. But America was entering an age of enlightenment, he promised. Times were changing.

This was, however, no feminist manifesto. Educated women had no need to become professors, or preachers, or politicians, Burroughs explained to the female students. Their newfound knowledge was bestused in the home to raise wiser children, especially boys, and make women better companions to men. Indeed, Burroughs noted, better educated women might also find it easier to enter the gates of Heaven.

Portsmouth Lyceum 2.0

Rev. Orange Clark, it appears, had borrowed only the name and a few elements of Josiah Holbrook’s groundbreaking lyceum concept. By 1833 the rebooted Portsmouth Lyceum was fully onboard with Holbrook’s vision. Speakers were selected from the best and brightest men of the Piscataqua community. Rev. Burroughs, of course, would deliver many lectures in the years to come.

The kick-off speaker was an aging Portsmouth customs collector name Andrew Halliburton. Speaking from a small stage lit by smoky gas lanterns, Halliburton addressed the importance of oxygen to the composition of clean air. Portsmouth Journal editor Charles A. Brewster gave his lecture on the printing process, which he then published for sale as a pamphlet. Dr. Charles Cheever told a packed house that the “science” of Phrenology could predict a man’s intelligence and moral character by examining the shape of his head. Other topics in the early series included: zoology, painting, how the mind works, how blood circulates, the history of money, the U.S. Constitution, horticulture, and the characters of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

The Portsmouth Journal rejoiced in the creation of the new lyceum, but wished there were more young men in the audience. The Portsmouth Cornet Band that preceded each talk was enjoyable, but the backless seats were uncomfortable. The big problem according to the newspaper,were the stylish ladies wearing large straw hats called “leghorns” that blocked everyone’s view of the speaker.

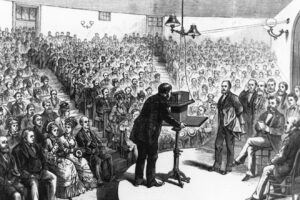

The Tuesday night lectures, sometimes accompanied by exciting demonstrations, readings, and visual aids, were often sold out. For decades the lyceum, essentially adult education classes, combined the familiar elements of church sermon, school, town meeting, and the theater into a single social gathering. Young men who purchased tickets could bring along two women. Hecklers, loud talkers, and those who wandered around during lectures could be ejected, the newspaper warned.

The Camenaeum

I knew, from years of pouring over old newspapers, that the Portsmouth Lyceum was held for many years at “The Temple” on Chestnut Street, the site of the Music Hall today. Originally constructed as a Baptist church in 1808, the Temple was later adapted into a lecture hall. The owners ripped out the church pews and replaced them with curved amphitheater seating. The Temple could accommodate 800 people comfortably, or 1,000 uncomfortably.

But I did not know, until I dug deeper, that the Portsmouth Lyceum started out in a forgotten theater just two blocks away. Erected as a Universalist Church in 1784, the building stood on Vaughan Street (now Vaughan Mall) at what is currently the Worth Parking Lot. Remodeled by investors, the church was adapted into an intimate 400-seat theater, ideal for the experimental lyceum lecture series.

In 1839 the city’s foremost church singers formed the Portsmouth Sacred Music Society and purchased the building. They installed an enormous pipe organ. Its 600 pipes ranged in height from three-quarters of an inch to 17 feet tall. Rev. Charles Burroughs called it “The Cameneum,” a fake Greek-sounding word loosely translated as “Home of the arts and Muses.” It was a terrible name, but it stuck.

Literary luminaries including Nathaniel Hawthorne and Oliver Wendell Holmes spoke at the Cameneum. President Franklin Pierce attended a concert there. The theater went through a final facelift at the hands of a talented but temperamental local teacher, painter, poet, and organist named Thomas P. Moses. Moses added an art gallery, painted celestial scenes on the ceiling, and increased Cameneum seating to fit 600.

But competition from The Temple, with better and expanded seating may have been too much. The Portsmouth Lyceum moved to Chestnut Street around 1854. A decade later the Cameneum was turned into a stable and a parking lot for carriages. It burned in 1883. Thirty sleighs and carriages, 40 tons of hay, and 24 horses with consumed by the blaze.

From the ashes

The popularity of lyceum lectures parallels the rise of many American reform movements prior to the Civil War. Evolved from church sermons, these talks often centered on moral issues. Reformers railed against perpetuating slavery, consuming alcohol, eating meat, the rise of capitalism, the failure of elite colleges, the treatment of women, and the exploitation of laborers. A lyceum lecture on the discovery of the planet Neptune or a demonstration of electricity or photography was sure to sell out.

But American audiences, increasingly mobile, educated, and gainfully employed, also wanted to be entertained. Portsmouth audiences flocked to see Frederick Douglass, a former slave, when he spoke at the Temple in 1862 on the future of black Americans. But they also wanted to see Signor Blitz, a popular ventriloquist and hypnotist. And they applauded with equal enthusiasm as white singers in blackface performed in racist minstrel shows.

The most popular performers who sold the most tickets got the best gigs as they travelled the “circuit” from town to town and hall to hall. Public speaking evolved into a profession for pop stars like naturalist Henry David Thoreau, comedian Artemus Ward, novelist Mark Twain, abolitionist Sojourner Truth, women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony and hundreds more. Portsmouth-born writers James T. Fields and B.P. Shillaber were among the “Kings of the Platform,” who saw lecture fees rise from $5 per talk to $100 (worth $2,000 today.) Ralph Waldo Emerson, who gave upwards of 1,500 lectures, could command up to $500 as he preached his inspirational message of independence self reliance to countless thousands at lyceums across the nation.

The Temple on Chestnut Street was consumed by fire in 1876. By then the lyceum movement was fading and a new craze called “vaudeville” was on the horizon. What Portsmouth needed was a classy, beautiful, modern, purpose-built theater. Rising from the ashes of the Temple, the Music Hall opened in 1878–and the rest is history.

Hall Jackson was a Revolutionary First Responder

Hall Jackson was a Revolutionary First Responder

Leave a Reply