The best Christmas bird story is a little-known poem by Portsmouth-born writer Celia Thaxter (1835 – 1894). The “Poet of the Isles of Shoals” is best known for “The Sandpiper.” another ornithological verse. Thaxter frequently wrote poems about birds – the kingfisher, the butcher bird, and the burgomaster gull among them. But her brief piece about a tiny swallow and a poor girl named Piccola was once an American classic, and deserves a fresh new look.

Poor little Piccola

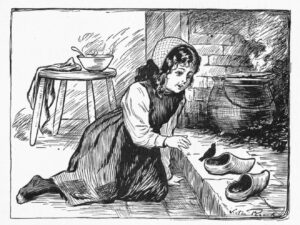

“Piccola” is Thaxter’s story of a French girl (although the name is usually Italian). Piccola’s family is so poor that her parents cannot afford a single Christmas gift for her. But Piccola has absolute faith that St. Nicholas will bring her a gift. She leaves out her tiny wooden shoe to receive the gift and then goes happily to bed on Christmas Eve.

It isn’t the best poetry. Thaxter’s rhyme and syntax are shaky, her words twisted to fit the meter. But she captures the drama and holiday spirit perfectly. We can all identify with the child’s unbridled excitement and with her parent’s guilt and concern. Celia Thaxter describes the gray skies that break on Christmas morning. We find little Piccola “just wild” with anticipation. She runs to see what the good saint has left in her shoe, but we know there is nothing there.

Yet she dances into the room “happy as a queen,” Thaxter writes, and “never was seen such a joyful child.” The reader wonders – how is this possible? (And how come our children get every costly toy today and still come up bored and wanting more?) Then the poet makes us wait an additional stanza, pulling us into the next room with Piccola’s confused parents. There we discover that “a little shivering bird” has flown in through the window and is resting in Piccola’s tiny shoe.

The child is enraptured with the gift. What the reader sees as a coincidence or a miracle, Piccola sees as a validation of her good behavior in the eyes of St. Nicholas. The sparrow is a living reward, better than any manufactured toy, and she accepts it fully with a thankful heart. This is the “spirit of Christmas” in action, the miracle of hope, giving, and thankfulness. Thaxter, who once met writer Charles Dickens, accomplishes her own emotional ‘Christmas Carol” in just 36 lines of poetry.

Celia the naturalist

We know Celia Thaxter as an author and a painter, as the hostess of her family’s Appledore House at the Isles of Shoals, and as the keeper of her famous island garden there. From her earliest days growing up beside the White Island lighthouse, she was a born naturalist too. She picked wildflowers, gathered sea moss and shells, studied the weather, and came to know the birds that found their way to her small rocky planet 10 miles offshore.

In her later years Thaxter campaigned against the use of bird feathers in women’s hats. She wrote to a friend: “I cannot express to you my distress at the destruction of the birds. You know how I love them; every other poem I have written has some bird for its subject, and I look at the ghastly horror of women’s headgear with absolute suffering.”

Thaxter became secretary of the Audubon Society in Waltham, Massachusetts in 1886. She wrote an article for the first edition of Audubon Magazine entitled “Women’s Heartlessness.” In the article she mourned the fact that the beauty of birds made them a target for human vanity. “Ah me,” she wrote as if speaking to an oriole, “your dead body may disfigure some woman’s head.”

McGuffey’s millions

Increasingly known as a writer for children, Thaxter evangelized her affection for birds in scores of poems published in magazines and books for young readers. Her poem about Piccola and the sparrow was selected to appear in McGuffey’s Fourth Reader, the most influential school textbook in America in the 19th century.

William Holmes McGuffey (born 1800) became an itinerant teacher in his early teens. He popularized the concept of “graded primers,” early textbooks designed to become more complex as students advanced through school. The first series of four volumes was published in 1836.

McGuffey’s books are still popular today among families with homeschooled children. McGuffey was also interested in moral education and for his advanced primers he often included reading selections from the Bible, or from notables like Milton and Shakespeare. Celia Thaxter, born on Daniel Street in Portsmouth in 1835, was homeschooled by her parents at the Isles of Shoals, and likely knew McGuffey’s readers well.

It is equally likely that William McGuffey never saw Thaxter’s poem. He died in 1873 and “Piccola” appeared, appropriately, in the popular children’s magazine St. Nicholas in November 1875. Later editors (Harriet Beecher Stowe who knew Thaxter was among them) added the poem to the 1879 edition of McGuffey’s Fourth Reader and it was included in Thaxter’s own poetry collection Drift-Weed the following year in 1880. “Piccola” continued to appear in edition after edition of McGuffey’s, often with new illustrations, and was popular well into the 20th century.

Untold thousands of school children read the poem aloud or heard it recited by their teacher. They discussed the vocabulary words in the text and answered questions following the poem, like “Who was St. Nicholas?” and “What did Piccola find in her shoe?”

In 1914 writer Frances Jenkins Olcott adapted Celia Thaxter’s poem into prose for an anthology including 120 stories about American holidays. In Olcott’s version, Piccola’s mother is a widow forced to work in the fields and unable even to buy bread. Piccola nurses the sparrow through the winter and teaches it to peck crumbs of food from her lips. She releases the bird in the spring, but it continues to live outside her window and sing to her. The added details do nothing for the story and the drama of Thaxter’s well-crafted poem is lost in translation.

McGuffey’s Reader sold an estimated 120 million copies in its peak years, even more than the Da Vinci Code today. But the story of poor Piccola, Celia Thaxter’s Christmas masterpiece, has simply flown away.

Copyright © 2010 by J. Dennis Robinson, all rights reserved.

BONUS: A 1921 Student Study Guide to “Piccola” by Celia Thaxter

From: Essentials of English: Lower GradesHenry Carr Pearson, Mary Frederika KirchweyAmerican Book Co. (1921)

—————————–

First Stanza. This stanza introduces Piccola and tells you where she lives.

Second Stanza. This tells when the story happened and what kind of parents Piccola had. Instead of telling you how hard her parents worked to keep hunger and want away from their home, the poem says that they could hardly keep the wolf from the door. This means the same thing. Why is it easier for poor people to live in the summer time?

Third Stanza. This stanza tells how the parents felt at Christmas time.

Fourth Stanza. Read the stanza that tells how Piccola felt.

Fifth Stanza. What did Piccola do on Christmas eve that shows she expected a present? Read the lines that tell about Piccola’s getting up and going to her shoe. How do you know it was very early? 1

Sixth Stanza. Can you imagine how sad her father and mother must have felt when they heard their little girl going to look in what they thought was an empty shoe? What did Piccola’s sounds of gladness tell them?

Seventh Stanza. What was the great surprise that Piccola found? How had it come there? What did Piccola think?

Who is the author of this poem?

STORY-TELLING FROM A POEM

Have you a good picture in your mind of little Piccola? See how well you can tell her story, not in verse as it is told on pages 125 and 126, but in good prose sentences of your own.

You might begin:

Far off in France there once lived a little girl whose name was Piccola. Piccola’s father and mother . . .

Go on with the story, trying to make your listeners see how poor the father and mother were and how sad because they had no present for their little girl. Let your voice and manner show how happy Piccola was when she found the bird in her shoe.

There are some words in the poem that you may want to use in telling your story. Sprang, shivering, peep, and crept are good words for you to use.

When you have practiced telling the story of Piccola in school and can tell it really well, tell it at home to your mother and father.

PICCOLA: Written Exercise

Finish the following sentences so that they will tell the story of Piccola. How can you find out how to spell the words without asking your teacher? Do not try to do too much at a time. Write Lesson I one day and put it away carefully so that on the next day you can write Lesson II on the same paper.

LESSON 1

Piccola was a little girl who lived in

Her parents were so poor that

When Christmas drew near they felt sad because ——But Piccola was sure that

LESSON 2

Before she went to bed on Christmas eve she

Early the next morning she

Soon sounds of

Down in the toe of her tiny shoe

Little Piccola believed that

Make the very best sentences that you can and write them carefully. Wouldn’t you like to illustrate this little story? You might draw on your paper Piccola’s little shoe with the bird peeping over the top or you might draw Piccola herself.

Group Exercise

When your papers are finished, ask your teacher to let you post them in the front of the room. Then look them all over carefully and vote for the five or six best-looking papers. Ask your teacher to see whether these papers sound as well as they look, that is, whether the sentences are as good as the writing and the illustrations.

Perhaps your teacher will let these very good papers hang in the room for a week so that every one who comes in can see what careful workers her pupils are.

Daguerreotype Reveals Face of Revolutionary War Soldier

Daguerreotype Reveals Face of Revolutionary War Soldier

Leave a Reply