What we don’t know about Prince Whipple would fill a book. As with millions of other enslaved Africans, we don’t even know his real name. Black abolitionist William Cooper Nell suggested Prince was born in West Africa, probably around 1750. When he was 10, the boy’s “comparatively wealthy parents” sent him to America to be educated. Bad idea. The boy and a cousin were kidnapped and auctioned like cattle at a Baltimore market.

The two boys were purchased and enslaved by William Whipple Jr., a successful merchant and ship captain from Kittery, Maine. Whipple married his cousin Catherine Moffatt in 1767 and two years later they moved into what is now the Moffatt-Ladd House on Market Street in Portsmouth. William Whipple went on to serve in the Continental Congress. He signed the Declaration of Independence and played a significant role in the American Revolution.

Gen. Whipple’s activities during the Revolution are well documented. But what his body slave Prince Whipple was doing is a blur, which is why 19th-century historian William Nell made a big mistake in his brief biography of Prince. And 20 years ago, after reading Nell’s book, I unwisely turned that error into an internet meme. We’ll get to that later.

From footnote to freedom

William Whipple’s place in American history was guaranteed along with the 55 other white male signatories of the Declaration of Independence. Prince and his cousin Cuffee Whipple were remembered in Portsmouth, primarily, as two talented musicians who performed for wealthy white guests at the gala dances at the Assembly House. Prince died in 1796 and became an all-but-forgotten footnote in Portsmouth history.

Then, in 1855, William Nell included Prince in his groundbreaking book, “Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.” Nell noted Prince was “much esteemed” and “beloved by all who knew him.” In his book, Nell recounted a story in which Prince was entrusted to carry a large sum of money from Salem to Portsmouth. Nell wrote: “He [Prince] was attacked on the road, near Newburyport, by two ruffians; one he struck with a loaded whip, the other he shot, and succeeded arriving home in safety.”

Prince was stereotyped in Portsmouth history as the ideal negro servant–loyal, efficient, attractive, polite and otherwise invisible. Local newspaper editor Charles Brewster offered a few paragraphs about Prince in his “Rambles About Portsmouth.” Brewster listed Prince’s date of purchase by the Whipple family as 1766 (six years later than Nell’s date) and referred to his cousin, Cuffee Whipple, as his brother. Although he never met Prince Whipple, Brewster described him as “a large, well-proportioned, and fine looking man” who carried himself like a gentleman, and was “prominent among the dark gentry of the day.”

Brewster also popularized the legend that Prince, at first, refused to join William Whipple who had been appointed as a brigadier general in the bloody Revolutionary War. “You are going to fight for your liberty,” Prince reportedly told Gen. Whipple, “but I have none to fight for.”

“Prince,” the general is said to have replied, “behave like a man and do your duty, and from this hour you shall be free.”

To attain his freedom, Prince relented. He was at Gen. Whipple’s side during campaigns against the British at Saratoga and Rhode Island. But he was not immediately set free. Back home by 1779, Prince and 19 other enslaved Portsmouth-area men petitioned the New Hampshire General Assembly for their freedom. Their petition was ignored.

On Feb. 22, 1781, Prince married Dinah Chase, who was enslaved by a minister from New Castle. Despite Gen. Whipple’s legendary promise, Prince was not legally manumitted until 1784, a year after the Revolution ended, and just a year before William Whipple’s death.

Prince, Dinah and Cuffee moved into in a small two-story dwelling on a lot behind the Moffatt-Ladd House garden. In 1905, long after his death, Prince Whipple was recognized by local veterans as “New Hampshire’s foremost, if not only colored representative of the war for Independence.”

Despite being recognized as a war veteran, Prince Whipple remained a sort of cartoon sidekick to General Whipple well into the 20th century. In 1964, for example, local historian Dorothy Vaughan wrote a glowing speech about the life of the heroic William Whipple. In Vaughan’s essay, delivered to The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America, Prince appeared “tagging at the heels” of the famous founder. At Gen. Whipple’s wedding, Vaughan wrote: “Close behind Mr. Whipple were his two slave boys, Prince and Cuffee, who went everywhere their master went. Tonight they were dressed almost as elegantly as the groom and their black faces glowed in the candlelight.”

Vaughan repeated the false story that William Whipple released Prince from bondage, before going into battle. “From this moment on you are a free man, Prince,” Vaughan quoted the general. “Hurry up now, and we will fight for our freedom together.” But Dorothy Vaughan was not the only historian to spread fake news. William Nell and I must also plead guilty.

Not crossing the Delaware

According to abolitionist William Nell, Prince Whipple is the one shadowy black figure pulling at an oar in the famous painting, “Washington Crossing the Delaware.” Not true. We can easily see why Nell jumped to this false conclusion. The patriotic painting by German-American artist Emanuel Leutze was released to ecstatic praise in 1851 when Nell was researching his book about “colored patriots.” The enormous canvas still seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art is more than 12 feet high by 21 feet long.

But the painting is symbolic, not factual. It shows a godlike George Washington standing amid his ragtag Continental soldiers en route to a daring attack on British mercenaries in 1776. Critics note the dawning light, the enormous chunks of ice, the flag, the size of the boat, Washington’s stance, Washington’s uniform, the lack of falling snow, and the width of the river in the painting are all inaccurate.

In 1997, when I started writing about Portsmouth online, I met Valerie Cunningham who, literally, changed the face of local history. After 20 years of painstaking research, she introduced the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail that includes her stirring account of Prince Whipple.

Inspired by Cunningham’s African-American history trail, I read William Nell’s book. Then I wrote online that Nell’s theory that Prince Whipple from Portsmouth might be the black figure in the boat with George Washington. My bad. The blowback was considerable. Among many critics, Blaine Whipple, the author of an enormous history of the Whipple family, wrote to correct my article. William Whipple, he explained, was 130 miles away in Baltimore while Washington and his starving troops were crossing the Delaware River. Prince could not be in the painting. I posted Blaine’s letter on my website with a promise to correct my original story. I didn’t get around to it for nine years.

A lot happened in that decade. The web grew up. What was a slow clunky operation in 1997 had become a fast and ubiquitous internet. America was looking for black heroes and a brand-new search engine named Google began sending millions of visitors to my website starting in 1998. In their book “Black Portsmouth” (2004), Valerie Cunningham and co-author Mark Sammons clearly stated Prince was very probably not at Valley Forge and not the man in the painting. But they reminded us that, not one, but at least 180 African-Americans from New Hampshire–almost one-third of the state’s enslaved population–served in the American Revolution.

The take-home point is clear. There were, for the record, at least 20 black men fighting for American independence among Washington’s soldiers who crossed the Delaware River that night. As many as 9,000 black soldiers, freed and enslaved, fought in the Continental Army and Navy, in state militia groups, as privateers, as servants to officers, and as spies in that war.

But fake news is impossible to fully retract. Websites and even history books across the nation still reference my 25-year-old essay suggesting Prince crossed the river with POTUS. While Wikipedia and many other online sources currently dispute William Nell’s theory, many historians, schools and reputable sources have yet to get the memo. So here it is again.

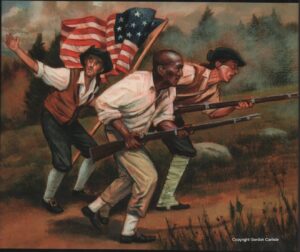

Nothing in Leutze’s famous painting is really real. It is an allegory. Washington represents America. The figures in the boat represent a wide range of Americans, including a frontiersman, and perhaps a woman or Native American. The black man represents black America, struggling just to stay alive, overshadowed, but present. In a pure and simple way that every heart can understand, he is Prince Whipple, and he is also every other patriot of color who fought for freedom and dignity in the American Revolution and in every war since. He is every African-American who continues to fight in the battle for equality that rages on and on with no end in sight.

READ ALSO: For a thrilling fictionalized account of another African-American soldier from Portsmouth read Stephen Clarkson’s “Patriots’ Reward” (2007, Peter Randall, Publisher) now available in hardcover and ebook formats. Thanks to Mr. Clarkson and artist Gordon Carlisle for use of the artwork accompanying this article. This essay is copyright 2018 by J. Dennis Robinson, revised 2025, all rights reserved.

A Scrapbook of Lost Children

A Scrapbook of Lost Children

Leave a Reply