Author’s Note: In 2021, the exhibition “abstracting the Seacoast” created an opportunity site down with top local artists and ask the question: What is abstract art? What began as a tugboat, bridge, seascape or street becomes an exploration of color, shape, and texture.

We gathered at the Portsmouth Athenaeum. Barbara Adams, Dustan Knight, Tom Glover, Peter Cady and settled into chairs around a long table. Brian Chu, the fifth member of the team, would later connect by phone.

“I really like this show,” I told the group, but I wasn’t sure why. The skills of the artists are palpable. Vibrant colors leap off the walls of the Academy Gallery, once a centuries-old school building and library, now restored by the Portsmouth Historical Society. Three major exhibitions in this gallery have featured traditional figurative works by Edmund C. Tarbell of New Castle and his students from the Boston School of American Impressionism.

While the “Tarbellites” painted within a strict set of rules, to my untrained eye, the five painters in “Abstracting the Seacoast,” inhabit worlds of their own design.

“So what do you do exactly,” I asked the group, “and why do you do it?” At first, no one responded to my impertinent request.

Dustan Knight

“Okay, I’ll start,” Dustan Knight spoke up. “I think feeling is a big part. Rather than doing a photographic likeness, I’m more interested in my feelings about the subject.”

“So we’re looking at your feelings?” I asked.

Dustan agreed. A graduate of Pratt Institute in NYC and with a master’s degree in Art History from Boston University, Knight has moved from a career as an art teacher to embracing her own work full-time in her New Castle studio. Edmund Tarbell is among her family’s ancestors.

“My feelings about the tugboats is that they are massive workhorses. I love the power that they have and the simplicity,” Knight explains. She is attempting to translate, speaking through the medium of paint and canvas, her sense of these creatures looming out of the mist on a damp, dark night.

“I do that by having a really washy paint, so that it feels more organic and sensory,” Knight says of her tugboat images.

Barbara Adams

“We start painting because it’s fun,” Barbara Adams says. “Because we love doing it.” Involved in the arts for over 35 years, Adams has transformed her work through many themes, styles, media, and subjects. She embraced watercolors and pastels before becoming passionate about abstract creations in oil. A number of her paintings also feature the iconic tugboats.

“I find the intensity and richness of using a palette knife and color mixing-in to be compelling and joyful,” she says.

“But can one make a living at this?” I ask the group, an odd question, perhaps, from someone trained to read classical literature.

Tom Glover

Tom Glover, who holds a BFA degree in painting from the University of New Hampshire, has successfully built a career in the arts as a painter, teacher, restorer, and artist-in residence. He studied the work of master painters during his travels to Italy, England, Ireland, France, and Denmark.

“I had an advisor that I went to as a freshman art student,” Tom Glover says from across the table. He recalls asking for advice on turning painting into a career. “Marry rich,” his advisor suggested.

Peter Cady

“People look at something that’s abstract and some of them walk away. That’s fine,” Peter Cady adds. “Other people want to try to understand it more. They’re the ones I’m interested in. Life is about learning new things.”

A Seacoast native, Cady studied civil engineering, but preferred working with his hands. He turned to fine woodworking and built his own timber-framed house. He made furniture, evolved into creating sculpture, taught science to middle school students, and has returned to a life of fine arts.

Perhaps, I suggest, as viewers, we often put too much effort into wondering exactly what the artist is trying to say instead of simply feeling and enjoying the work.

“It’s not a verbal medium,” Cady says. “It’s visual.”

“You have to invest if you want to understand,” Glover agrees. “Abstract art doesn’t come from nowhere. There’s a huge body of work that this all develops from. That’s the historical part.”

“But the general viewer doesn’t know all that history,” I say. “So then is abstract art only for abstract artists?”

“No,” Dustan interjects, because the work speaks emotionally to all audiences. “That emotional expression invites the viewer to spend more time with the picture and to tap into their own feelings,” she says.

“I don’t think everyone who comes to see abstract art wants to understand it,” Barbara Adams says as our discussion grows more lively. “A lot of people love the intense color, or maybe the composition makes you feel good. It’s pure response.”

“So there’s emotion captured in that paint?” I ask, not sure if the question is dumb or clever.

Dustan smiles. “It’s done with color,” she says. “It’s done with black and white values. It’s done with the texture of the paint and how the paint is put onto the canvas, with the speed and regularity with which the paint goes on. It’s done in the way the brushstrokes are arranged — or whether there are any brushstrokes.”

“So it’s a language?” I ask. There are nods around the table.

“It’s a visual language,” Adams adds. Colors affect people. Shapes affect people. Texture affects people.

It’s a universal language, we agree, an instinctual, reactive, and wordless language. Our job as viewers may simply be to react, rather than understand.

“So it’s more like poetry,” Dustan says.

“It’s very much like poetry,” I agree, bending the conversation back to literary territory I’m familiar with, “but it’s poetry without words.”

There’s also a wordless conversation going on between the artist and the art, Peter Cady explains. “The artist does something. The painting talks back. The artist adds or takes something away, and the conversation continues.”

“That’s the artistic process,” Glover agrees. “It’s a conversation.” The artwork talks with the artist who speaks to the viewer, all in silence.

I think I’m getting it. During my next visit to “Abstracting the Seacoast,” I vowed to react more and struggle to understand less.

But first I want to hear from the fifth member of the team. Prof. Brian Chu grew up in Taiwan. He spent 14 years in New York City, lived in Georgia and Pennsylvania, and has been teaching studio art at UNH for the last two decades. His wife Shiao-Ping Wang is an abstract artist.

Brain Chu

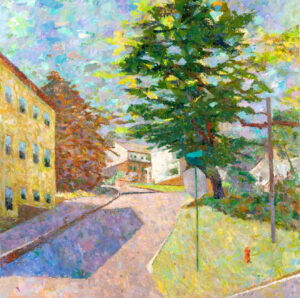

“I like to show with my fellow artists in this region,” Chu says was his primary reason for appearing in the exhibition. He describes his work here as more representational and impressionistic than abstract. He also uses the phrase “observational.”

“When we look at your paintings,” I ask, “you were there, right on scene?”

“Yes, I only paint on location at the start. I don’t work with the photograph,” Chu says. “Then I work in my studio. Many times I need a gap. I need time. A year later I’m more able to work on them. At that moment the color relationship and the movement [in the painting] is getting stronger. It takes a long time.”

Pressed further to describe his own work, Chu selects the term “duality” that he defines as “a two-dimensional thing with a three-dimensional sensation.” There is movement within the stillness, I believe he is saying, if only we learn to see it.

Our conversation drifts back to the silent “language” of painting. Like his fellow painters, Chu implies, I may benefit more by experiencing abstraction than by trying to define it. “In a way, seeing itself is abstract,” Chu says, “and the term changes with each generation.”

“So you would agree with Dustan Knight,” I ask him, “that we are looking at a picture of your feelings?”

“Correct,” Brian Chu says with no hesitation. “But I think the major emphasis of this exhibition is seeing these individuals having a show together. To me, that is the real key.“

Copyright J. Dennis Robinson

Directing the 1986 Little Italy Reunion

Directing the 1986 Little Italy Reunion

Leave a Reply