(Strawbery Banke Museum Collection)

“Painting is dead!” a French artist exclaimed in 1839. The first successful photographs by inventor Louis Daguerre shocked Europe and would quickly change the world. At 7 a.m. on Sept. 10, 1839, the secrets to the photographic process arrived in New York aboard a transatlantic steamer. American entrepreneurs immediately scrambled for ways to duplicate and improve the process – and turn it into cash.

A few months later, on Feb. 22, 1840, the Portsmouth Journal reported that “the greatest discovery of the age” had come to town. Samuel P. Long, a local artist, was exhibiting a photographic “sketch” made of the Universalist Church (no longer there) on Pleasant Street in Portsmouth. The extraordinary image, created by light etched via chemicals onto a sheet of metal, clearly showed the sash of the church steeple and the naked limbs of an elm tree. Long offered a public lecture and demonstration of the process two weeks later at the Portsmouth Academy, now Portsmouth Historical Society.

Samuel Long typifies the pioneers of early photography in America. Born in Portsmouth in 1797 (when George Washington was still alive), he started out as a lawyer, but found the career “distasteful.” He wanted to be creative. Making a living at writing and painting, however, was as difficult then, as now. Long was drawn to the magical and exciting craft of photography. Sadly, none of his photos and only one of his paintings survives.

No comprehensive study of Portsmouth’s founding photo-fathers has yet been assembled, so this history comes to us in scraps and notes. A dozen photographers dabbled in the new medium in Portsmouth in the mid-1800s. Like itinerant portrait painters and silhouette artists, which some also were, these men set up shop, played out the local market, and moved on. Williams Snell, for example, was in town during June and July of 1842, then gone. He then pops up in the records of Newburyport, Salem, and Beverly, Mass.

In July 1848, Francis Ham snapped one of the most historic images in Portsmouth. George Fishley, among the last of the city’s “cocked hats,” sat for his portrait wearing his Revolutionary War-era uniform. Born in 1760, Fishely joined the American Revolution at age 17 and fought under the command of John Sullivan, Enoch Poor, Alexander Scammell, Henry Dearborn and George Washington. As a privateer in 1781, Capt. Fishley was captured and spent time as a prisoner of war in Halifax. Fishley was among a handful of soldiers from the Revolution who lived long enough to be photographed, and his daguerreotype was rediscovered at the Portsmouth Historical Society about 15 years ago.

Taking portraits indoors before electricity required large windows and top-floor skylights, so a series of photographers often rented the same rooms. Francis Danielson set up his “Daguerrian Gallery” downtown in the 1850s, but did not last long. German immigrant Peter Salen took over the same well-lighted studio, but soon moved on.

The year after shooting Capt. Fishley, Mr. Ham moved his studio from Congress Hall to Congress Street. Albert Gregory, among the finest early photographers, also opened his studio on Congress Street in the early 1850s. Gregory is best known for his photograph of “Old Ironsides” being repaired at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in 1855, one of the oldest images in U.S. Navy history. Gregory photographed the giant ceremonial arches constructed in Market Square for the homecoming celebration of 1853. It was adapted for publication into an iconic illustration.

Carl Meinerth comes and goes

A rare Portsmouth image barely two-inches square was recently acquired at auction by the Portsmouth Athenaeum. The work of Carl Meinerth depicts a building under construction surrounded by lumber and scaffolding. An unknown man stands to the right. Expert analysis proved it to be the Frank Jones malt house being built in Portsmouth’s West End during the Civil War in 1863, an extension to Jones’ already expansive brewery.

A contemporary of Albert Gregory, Meinerth is best known for one of the earliest news photographs in the city. Upon hearing of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, grief-stricken locals held a mock funeral in Market Square in April 1865. Meinerth was there with his camera. Days before, locals rioted on Daniel Street and trashed the printing press of Joseph Foster’s pro-slavery newspaper. Although it is uncertain who took the famous picture, Meinerth’s studio was located just across the street.

Each rediscovered image fills in one more piece of the puzzle and shows us a Portsmouth often very different from the one we think we know. We owe a great debt to the city’s many entrepreneurs, but who were these men? Meinerth, thankfully, posed in front of his own lens. Although seated, he appears tall with a super-high forehead, a thick beard and thin wire-rimmed glasses.

Like his contemporaries, Meinerth was a born artist. He first advertised himself as a music teacher on Islington Street in 1849. By 1852, he was also teaching drawing lessons on Daniel Street. Ten years and five addresses later, Meinerth had a downtown photo studio, too. Besides being a virtuoso on the piano and violin, Meinerth was an avid naturalist and taxidermist who photographed scenes of stuffed birds and preserved insects and marine life. He moved his studio to Newburyport, Mass. where he died in 1892.

“Have you been taken yet?”

Beginning in the 1850s, anyone who was anyone had arranged a sitting with one of the local photographers. Few families had been able to afford painted portraits in the past. Now, beyond the living, photographers found a macabre group of new customers. A notice at the bottom of a local studio newspaper ad read: “Sick and deceased persons taken at their residences.”

While Louis Daguerre needed up to an hour’s worth of light to capture his first images in Paris, American innovators continued to reduce the exposure time and improve the quality of their product. Ambrotype images, developed in Boston, were printed on glass rather than the metal printing surface of daguerreotypes. They were less reflective and easier to view. But they still produced only one picture per photo (no negative to reprint from) and the mirror-image on the plate was reversed.

The familiar “collodion” process soon followed as did a boom in the portrait business. A glass plate coated in light-sensitive chemicals could now create a negative that could then be printed and reprinted onto light-sensitive paper. Albert Gregory and others swapped to the new system, but the market was heating up.

In 1861, Lewis Davis, originally from Ripley, Maine, partnered with his brother Charles in a company that preserved local history for decades to come. Their “carte de visite” prints, small photos backed on heavy paper, became the Facebook of the Victorian era. Affordable, portable and durable, they could be exchanged like business cards. The Davis Bros. also cashed in on the stereoscope craze in which two similar images, when viewed in a hand-held device, produced a three-dimensional effect.

By the end of the Civil War, photography was embedded in American culture. The Davis Bros. advertised “Pictures for the Millions” and operated from studios, first on Daniel Street and later on Pleasant Street. They flourished for 35 years until the influx of cheap personal cameras made picture-taking accessible to the masses. Charles Davis and his wife, Mattie, built a large home on Miller Avenue, while Lewis and Cyrena raised their family at the corner of Highland and Broad streets. As the Seacoast tourist industry expanded in the 1870s, thousands of Davis Bros. souvenir cards depicted memorable scenes from Hampton Beach and the Isles of Shoals to York, Maine.

Lafayette Newell captured the city

Lafayette Newell was a Barnstead farm boy, one of 13 children, who trained as a photographer in Concord in the mid-1850s. During the Civil War, thanks to the influence of his twin brother, Albert, Newell was offered a position taking photographs at Point Lookout, Md. where Union soldiers guarded 25,000 Confederate prisoners of war. After the war Newell carefully transported hundreds of irreplaceable glass negatives to Bow Street in Portsmouth where his wife’s father owned a grocery store. Newell, then employed as a teacher of handwriting, stored his historic photos in the attic of the store. But vandals found the fragile plates and smashed every one.

At age 35, despite the loss of his historic collection – or maybe because of the tragedy – Newell started over. For the next three decades, with a distinctively artistic eye for lighting and design, he captured scenes of Portsmouth and the surrounding area. His son John Newell inherited the amazing collection.

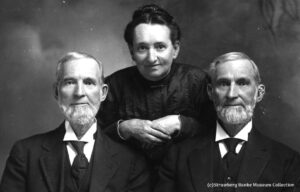

Newell’s photos passed to former bordello owner “Cappy” Stewart, who ran a riverside antiques shop. Garland Patch, a welder at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, bought Newell’s photo collection from Cappy’s South End shop. Patch later sold much of his private archive to Strawbery Banke Museum in 1970, where they are preserved today.

Some of the most provocative views of the city in its Victorian era come from Newell’s later work.

By the turn of the 20th century, visitors and locals could “Kodak” their own memories. Stereographs were slowly replaced by souvenir “viewbooks” and penny postcards. But no survey of Portsmouth photography is complete without a nod to Caleb Stevens Gurney and his book “Portsmouth Historic and Picturesque” (1902).

Gurney’s comprehensive coverage with 400 images went far beyond the standard scenic viewbook. He combined a written history of Portsmouth, borrowing from the works of Charles Brewster and Sarah Haven Foster. He included older photos taken by Newell, the Davis Bros., and others. In addition to his own photos, he catalogued most commercial and historic buildings, listed historic events, and added maps.

Like his predecessors, Caleb Gurney was a creative character in search of a commercial success. He was born in Hebron, Maine, in 1848. While his wife, Laura, held down a manager’s job at shoe factories in Kennebunk, Maine and later Portsmouth, Caleb pursued a freelance career in photographic “artwork.” In 1892, he formed the Acme Portrait Company at 8 Market St. After publishing “Historic and Picturesque,” he opened the Gurney Ball Joint Umbrella Company at 74 Islington St. The umbrella company is long forgotten, but Caleb Gurney’s photographic labor of love stands the test of time, and remains a key visual guide for lovers of Portsmouth history.

KEY SOURCES: (1) Research materials provided by Richard M. Candee and Tom Hardiman; (2) introduction to “Historic Portsmouth” (revised 1995) by James L. Garvin; (3) introduction to “Around Portsmouth in the Victorian Era” (1997) by Ronan Donohoe and James Dolph; (4) introduction by Martha Fuller Clark to “Gurney’s Portsmouth: Historic & Picturesqe” (1981 reprint).

Copyright 2014 by J. Dennis Robinson, all rights reserved.

The Candidates at the Fair

The Candidates at the Fair

Leave a Reply