I was on a Zoom conference recently with a director whose last film was nominated for six Oscars including “Best Picture.” He was in Australia. I was in Portsmouth. His producer and scriptwriter were also on the screen from somewhere far away, along with a podcaster and crime writer from Durham. I had been asked to deliver some background on Portsmouth history, something I do via the Internet many times each week.

The meeting was no big deal, which is exactly my point. We routinely face off these days with people from around the globe. Our miraculous ability to talk to almost anyone from anywhere anytime barely quickens the pulse. Not so for the people of Rye on July 15, 1874.

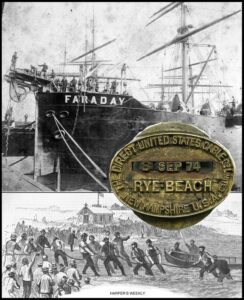

The crowds gathered off Jenness Beach were thrilled as they waited for the coiled two-and-a-quarter-inch thick wire to arrive from Europe. Running 3,400 miles under the ocean from Ballinskelligs, Ireland via Nova Scotia, the cable landed in New Hampshire at 9 p.m. Spectators who had been waiting for days only to find the delivery ship delayed by fog were served doughnuts and coffee by a local woman.

The cable-laying ship CS Faraday sat just off the Isles of Shoals. Local fishermen joined with male and female tourists from the Farragut Hotel. Wading into the surf, they hauled the heavy cable from the delivery barge to the Cable House, today converted to a private residence.

A national magazine reported: “It was a very dark night and the procession of boats with their lanterns formed a gloomy appearance as it moved through the stillness broken by the heave-ho of the cable hands and the wild uncouth songs with which they accompanied their clock-like motions as they worked along the ropes.”

The Rye, NH, transatlantic connection was not the first. In 1858, after multiple attempts, an underwater cable successfully delivered a telegraph message from Europe to Canada. It read: “Glory to God in the highest; on earth peace, and goodwill toward men.” Messaging was extremely slow and took up to two minutes to transmit each character. When engineers boosted the voltage, the cable failed.

The more advanced design of the Rye cable improved speeds and allowed messages to be sent in both directions. The transatlantic telegraph at Rye was instrumental in delivering news of the 1905 Russo-Japanese Treaty negotiations and survived into World War II. A small chunk of the 1874 cable can be seen at the Woodman Institute in Dover. During very low tides, remnants of the cable are sometimes visible, along with tree stumps from the prehistoric “Sunken Forest” at Rye Beach.

For much more information visit Atlantic-Cable.com. Copyright 2021 by J. Dennis Robinson, all rights reserved

Murder at the Home of NH’s Founder

Murder at the Home of NH’s Founder

Leave a Reply